The Fight for Farmed Animals

Students in the law school’s new Animal Law Litigation Clinic face off against industry and government to prevent animal suffering and protect the food supply.

by Daniel F. Le Ray

Every year, more than half a million pigs arrive at slaughterhouses around the country sick or severely injured.

Unable to walk, these “downed” animals sometimes carry human transmissible diseases such as listeria, campylobacter, swine flu, and salmonella. Dragged, kicked, and electric prodded, they are coerced through the slaughter process and killed alongside healthy livestock.

In 2002, Congress requested that the Secretary of Agriculture investigate and report on downed livestock. “It’s been almost two decades, and there is no indication that the agency ever studied nonambulatory pigs, despite pigs accounting for 75 percent of the livestock being slaughtered,” says Delcianna Winders, assistant clinical professor and director of the Animal Law Litigation Clinic (ALLC) at Lewis & Clark Law School.

In 2014, a coalition of organizations petitioned the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to ban the slaughter of downed pigs, citing human health and animal welfare concerns. Last fall, that petition was denied.

In a new case filed in February, the ALLC is now “challenging the agency’s failure to comply with Congress’ 2002 mandate to investigate, report, and regulate, and the denial of that petition.” The goal: to prevent further animal suffering.

Animal Law Fundamentals

Launched in fall 2019, the ALLC is the most recent addition to Lewis & Clark’s Center for Animal Law Studies (CALS). In 2008, CALS was created with the goal of becoming “a world-renowned epicenter in animal law,” according to its executive director, Pamela Hart. Its mission: to educate the next generation of animal law attorneys and advance animal protection through the law. In its first year of operation, CALS housed the only animal law clinic in the nation. Now it offers three. While the others focus on policy issues and international wildlife, respectively, the ALLC focuses on farmed animals.

“We set out to cultivate groundbreaking litigation and disrupt standard practices,” says Hart. “By all accounts, we are achieving that through our launch of the ALLC.”

“Farm animals are the most exploited animals on the planet in terms of numbers and in terms of the suffering they endure,” says Winders. Because livestock accounts for 98 percent of all human-animal interactions worldwide, they “intersect with every single type of law.”

In such a complex area of law, ALLC leadership is key. Winders’ impressive resume includes management positions with the PETA Foundation and Farm Sanctuary. She was also Harvard Law School’s first Animal Law and Policy Program fellow. But after a career fusing full-time practice with teaching and publishing, the role with the ALLC “just seemed like the perfect melding—it was a dream come true,” she says.

According to Pamela Frasch, professor and associate dean of Lewis & Clark’s animal law program, the addition of Winders allows “students to develop the intellectual tools to form sophisticated legal strategies while also learning essential litigation skills so that upon graduation they are ready to advocate immediately and effectively for animals.”

With its hands-on approach, the ALLC—which is one of 25 animal law class offerings—demands that students research and draft cases; interview clients; and represent clients in the courtroom. Each week involves a two-hour class, a meeting with a practicing attorney, and 10 hours’ work outside the classroom.

“Our mission is twofold: to advance the status and interests of farmed animals and to train the next generation of animal law attorneys.”

Case selection can be “a balancing act, because we’re focused on impact litigation that is going to help individual animals immediately but also effect broader change for farmed animals,” Winders explains. “I’m very mindful of what the learning opportunities are going to be for the students, because our mission is twofold: to advance the status and interests of farmed animals and to train the next generation of animal law attorneys.”

Law school dean Jennifer Johnson notes, “Animal law is an emerging field of law. Because of the vision of Professor Frasch in establishing the Center for Animal Law Studies more than 12 years ago, Lewis & Clark Law School is at the forefront of teaching, scholarship, advocacy, and litigation in this exciting area of legal studies.”

Cristina Kladis JD ’20 hopes to be part of this new field after graduation.

“I came to Lewis & Clark because of its joint specialties in environmental and animal law,” says Kladis, who previously worked as a journalist, helming a documentary film about the environmental impact of factory farming. “In most of my law classes, I read about the outcomes of cases and how courts came to those decisions. In the clinic, I’m actually involved in bringing cases.”

A Voice for the Voiceless

The downed pigs case is only the second filed by the ALLC. Although the clinic is not focusing exclusively on pigs, the first case, filed in December, also challenges USDA regulations surrounding pig slaughter. Last fall, the USDA deregulated pig slaughter by reducing federal oversight in slaughterhouses and removing the limit on how many pigs can be killed per hour, previously set at 1,106.

“This has pretty devastating impacts for the pigs, who are supposed to be ensured humane handling as well as humane slaughter, meaning that they’re rendered unconscious before their throats are slit,” Winders says. The ALLC case argues that these changes encourage inhumane treatment, since there is higher profit in high-speed slaughter. They will also result in the deaths of an additional 11.5 million pigs annually.

Mariann Sullivan, a professor of animal law at New York University, praises the ALLC’s work as groundbreaking.

“In the few short months it has been in existence, the clinic has brought two cases on behalf of pigs who are being abused in ways that are not only horrific, but which are very arguably not in compliance with the law,” she says. “If it were not for this clinic, these illegalities would simply continue, unaddressed and behind closed doors.”

Clinic students have been instrumental in drafting case materials and working with the coalition of plaintiffs. Winders expects that the USDA will ask the court to dismiss this particular case on “standing” grounds—that is, on the basis that the plaintiffs are not being personally injured by the challenged action—but “we have students working on a brief to oppose that anticipated motion, and also to do the oral argument in court.”

Students can participate in such litigation proceedings under special court dispensation, provided they are closely super- vised by an attorney. This presents a unique learning opportunity.

“More often than not, you can easily graduate from law school never having done many aspects of practice. The clinic experience gives students an opportunity, while they’re still in school, to gain practical legal skills, which makes them much more marketable,” Winders says. It also helps them explore their future careers—“because there are a lot of different ways of being a lawyer, and it helps them figure out: Do I want to be a litigator, or would I rather work on policy?”

A New Kind of Lawyer

Hira Jaleel LLM ’20 was a practicing attorney in her native Pakistan before enrolling in Lewis & Clark’s unique post-JD master’s program—the world’s first advanced legal qualification focusing on animal law. At home, she litigated some of the country’s first animal law cases, but she’s encountered a steep learning curve getting up to speed on U.S. legal practice.

“Professor Winders painstakingly takes the time to teach us about every aspect of being an attorney, from legal ethics to courtroom decorum,” Jaleel says. “As part of the clinic, we have undertaken media training, practiced oral arguments, visited court to observe arguments, and heard guest lectures from some of the leading professionals in the field.”

Jaleel hopes to return to Pakistan after graduation to continue her work in animal law, in the hopes of informing policy change.

Classmate Irene Au-Young JD ’20 says that “animal advocate powerhouse” Winders has created the right kind of space to encourage learning while pushing her students. “The program has exposed me to a variety of issues that are at the forefront of animal welfare, enabling me to participate in groundbreaking work that will catalyze positive change for nonhuman animals,” says Au-Young, who had initially intended on going to veterinary school.

One difficult aspect for all clinic students is divorcing their emotional reaction to animal suffering from their work on animal rights cases.

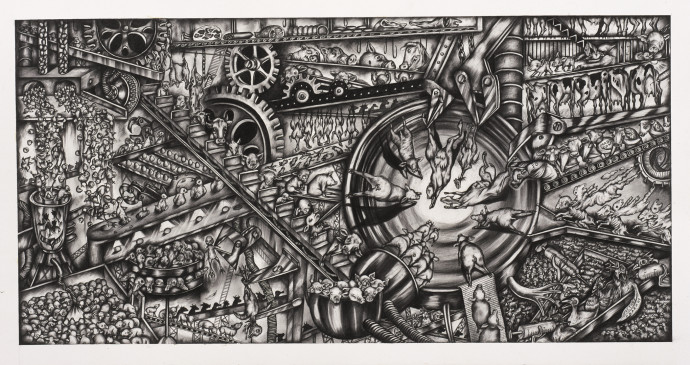

“One of the very first topics that we cover in our seminar during the school year is compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma,” says Winders. “It’s hard to see this imagery and to hear about the things happening to these animals. It’s a constant struggle. Learning to deal with the emotional aspects of this work is an important skill to teach our students. Many want to pursue careers in this field, but they can only do that if they don’t burn out.”

Students read about the topic, discuss ways of coping, and try to incorporate affective elements into their legal strategies. “I try to channel my emotions in a way that allows me to focus on the objectives of the particular case and the best possible outcome for the clients,” Au-Young says.

Fighting for Animal Rights

The two ALLC lawsuits to date target the USDA. “Some of our only laws to protect farm animals are delegated to the USDA, and they’ve done an appalling job of implementing and enforcing those laws,” Winders explains. “It’s important to hold them accountable.”

But often, these cases are an uphill battle: Courts grant deference to government organizations while big agriculture has massive resources at its disposal.

“People care about farmed animals and think they should be treated appropriately.”

“I have to prepare students for potentially losing the case and talk about what victory means in a broader perspective,” says Winders. “You might secure smaller victories that are helpful for the animals, even though they don’t get us all the way. It can be part of the impact litigation strategy itself.”

Another element is media attention. For example, the ALLC’s second case against the USDA received high-profile coverage in the Washington Post. Winders herself has written for multiple outlets, such as Newsweek, National Geographic, Salon, and USA Today. In some cases, even when lawsuits may not prevail, this press coverage is enough to force a change.

Even if people don’t really care about farm animals, there are plenty of reasons to be concerned about issues like downed pigs. Most people don’t want to eat meat sourced from sick or abused animals, and factory farming is one of the biggest contributors to climate change and pollution.

But even though “there are so many forces in play, including agriculture laws and efforts by industry, to keep us from knowing,” Winders says, the key is that most people do fundamentally care.

“If they see the videos and photos of these downed pigs, who are being kicked in the stomach and shocked with electric prods—most people don’t want that. People care about farmed animals and think they should be treated appropriately.”

Daniel F. Le Ray is an award-winning freelance writer and editor based in eastern Washington state.

More L&C Magazine Stories

Lewis & Clark Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

Lewis & Clark Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219