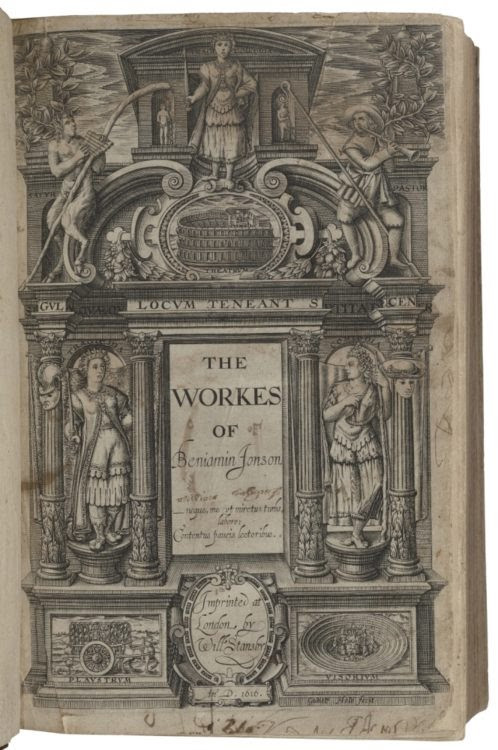

From the Archives: Ben Johnson, The Workes of Ben Jonson (1616)

The workes of Beniamin Ionson appeared in the fall of 1616 in a large, imposing folio volume. Running nearly 575 leaves, Ben Jonson’s Workes is a testament to his skills, popularity, but most primarily his determination to have his writings published together in a single volume, demonstrating his flexibility and progression as an English writer. At Lewis & Clark we use our copy of the folio - one of only two held at a liberal arts - to teach lessons about print culture in the sixteenth century.

Open gallery

The workes of Beniamin Ionson appeared in the fall of 1616 in a large, imposing folio volume. Running nearly 575 leaves, Ben Jonson’s Workes is a testament to his skills, popularity, but most primarily his determination to have his writings published together in a single volume, demonstrating his flexibility and progression as an English writer. At Lewis & Clark we use our copy of the folio - one of only two held at a liberal arts - to teach lessons about print culture in the sixteenth century.

Although folio editions - printed on larger, more expensive paper - were usually reserved for religious texts that were likely to sell, Ben Jonson, a poet and playwright who knew Shakespeare and enjoyed some of the same patronage, decided to commission his work in this format. It was unusual for the author themselves to register work with the Stationers’ Company, but this is what Jonson did in January of 1616. This gave him control over the work’s layout and changed the role of the author and playwright. While most playwrights at the time acted in their own plays and discarding their fowl papers (drafts of scripts) after the performance, Jonson took ownership of how they were ultimately saved and presented to the public. We can thus use the folio as a tool to study how Jonson thought about his own work and his status as an author.

The folio can be used to study the relationship between the quartos and later authorial volumes. In the Renaissance, quarto editions of plays were often pirated. People watching the play would write down the lines - or their closest memory of the lines - and hand them off to a printer to be circulated. This explains the huge disparities between the first quarto edition of Hamlet and all later versions. However, in the case of Jonson’s folio, several plays are clearly modeled on their quarto editions. For example, several errors in the quarto edition of Jonson’s Volpone are reproduced in the folio, indicating that the typesetter worked directly from these texts. Although Jonson is rumored to have visited the printing house twice a day to correct the text, these errors seem to have avoided his notice.

The folio changed the way people thought about early modern text and the authority of its creators. In many ways, it raised the status play texts to high art. It also offers a case study that demonstrates the workflows of early modern printing houses. At Lewis & Clark, we thus use it as a window to the Renaissance.

Aubrey R. Watzek Library is located in Watzek on the Undergraduate Campus.

email watzek@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7270

Aubrey R. Watzek Library

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road

Portland OR 97219