The Rise of Big Immigration Law

U.S. immigration law has always featured multiple paths to recognized membership in the U.S. polity: lawful entry at the outset, later legalization through deportation relief, regularly enacted legalization programs, and grants of asylum. The mushrooming of immigration policing strategies, however, threatens to narrow or even close these avenues to lawful status.

By Juliet P. Stumpf, Robert E. Jones Professor of Advocacy and Ethics

People are wrong about Donald Trump and immigration.

Trump’s presidential campaign explicitly targeted immigrants and immigrant communities of color. He promised to crack down on unauthorized entry and build a big border wall. He promised to implement mass detention to deter migration, and mass deportation of the millions of immigrants living in the United States without authorization. He said he would deport the “bad” immigrants, the dangerous and the criminal. His rhetoric painted Mexican and Muslim immigrants as criminals and terrorists, and immigrants in general as economic and cultural intruders. He promised to turn the tide from amnesty to enforcement. And as president, Trump has tried to follow through on all of these immigration campaign promises.

Trump’s Immigration Policies Are Not New

Where people go wrong is in assuming that this approach is something new. In fact, everything the Trump Administration is doing has been tried before.

Since the War on Drugs of the 1990s, the United States has been in the thrall of immigration policing strategies that rely heavily on large-scale detention and deportation. Congress expanded deportation grounds and swept away reasons to waive them. Before 1980, people were rarely detained. In 2014, the number of people detained surpassed 400,000. Removals of noncitizens rose from under 43,000 in 1993 to more than 430,000 in 2014. Funding for federal immigration enforcement is now 24 percent higher than funding for all other federal law enforcement agencies combined, and immigration enforcement agents constitute the largest armed federal force in the nation.

A New Phenomenon: Organized National Resistance at the Site

Traditionally, immigration practice in the United States has worked within—and in the direction of—networks of government power, oriented toward facilitating admission of noncitizens. As ballooning immigration policing resulted in skyrocketing detention and deportation numbers, immigration practice fell behind, leaving the majority of noncitizens unrepresented in immigration court. Deportations resulting from nonjudicial administrative processes, where attorney intervention was extremely rare, outpaced judge-ordered removals.

That is changing. Airport inspection sites and detention centers have become some of the places where immigration-inclusive policy and civil rights laws—and the individuals they are supposed to protect—have proven to be at greatest risk. In a development that doesn’t surprise anyone familiar with the social theories of Michel Foucault, those sites where government institutions most rigidly control movement and choice have given rise to resistance to these policies, institutions, and messages.

This is what is new in immigration law. Advocates for immigrant communities have been building a multilevel, multimedia, crowdsourcing advocacy structure that my colleague and I have dubbed the Big Immigration Law model. A counterpoint to the big immigration policing that has come to dominate American immigration policy, it consists of strategic, large-scale, localized, and nationalized networks opposed to enforcement practices that undermine immigration law.

What does an effective site of resistance look like? Our CARA Pro Bono Project case study (see the side bar) describes one. CARA arose in response to the mass confinement of children and mothers seeking asylum from persecution in the Northern Triangle countries of Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua.

The Future of Advocacy?

Can this model work in other contexts? We may have an opportunity to see. Big Immigration Law has gone on the road. Civil rights advocates are adopting these strategies in response to the vertebrae of private detention facilities rising along the U.S. border with Mexico, and to the reinstitution of home and workplace raids by federal immigration agents. The Innovation Law Lab, in collaboration with Causa and dozens of civil rights advocates, is constructing the infrastructure for an immigrant-inclusive Oregon. Lewis & Clark students, along with my colleagues and I, are providing inspiration and support.

The Trump Administration’s “new” ideas about how to detain and deport? That’s just old news in a bigger font. The real legacy of this president—whether he likes it or not—will be the construction of one of the largest and most effective civil rights networks in modern times.

-

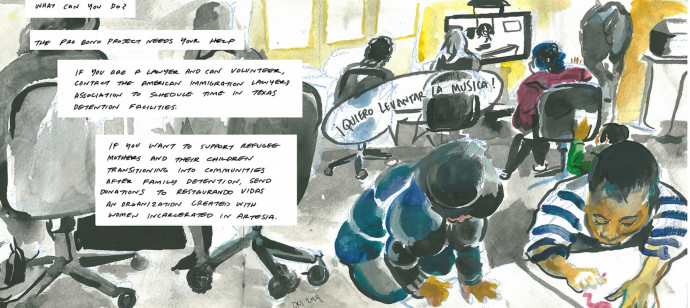

The CARA Pro Bono Project

In 2014, extreme violence arising from instability in the Northern Triangle drove families and unaccompanied children northward to seek safety.

Fearing that these families would derail progress on immigration policy, the Obama Administration changed longstanding policy from using an affirmative asylum process for families to a program of detention for mothers and children arriving together. The purpose was to deter other Central American families from seeking to enter the United States.

By deciding to detain the asylum seekers, the Department of Homeland Security chose to channel asylum adjudication for the mothers and children into the deportation system—where representation levels drop precipitously and approval rates plummet. Describing the families both as scofflaw economic migrants and as posing a national security risk, the DHS denied release on bond across the board.

As became clear later, detaining one individual in order to deter another is unconstitutional, the denial of bond unlawful, and the mass detention of children a violation of a longstanding settlement agreement.

For advocates, the challenge was how to remedy an asymmetry of power that came about because of a flaw in the system. To be effective at pushing back against the government’s unlawful actions, advocacy needed to accomplish three things:

- Change the narrative.

- Reveal the system flaw causing the problem.

- Focus resources—people, funds, technology, data—on remedying that design flaw.

These became the goals of the CARA Pro Bono Project.

Deconstructing the Traditional Representation Model

The success of the advocacy initiative relied on reframing how the public understood the legal basis for the families’ presence in the United States. Homeland Security told a powerful story about the national security threat that the families posed. But most Central American children and their mothers were seeking asylum from abuse by the mara—sophisticated, hyper-violent organizations that had established social control over whole geographic territories. Established domestic and international law allows individuals to seek asylum from within the United Stated, regardless of how they entered, because flight from persecution rarely leaves time for ordered immigration processing. Advocates needed to shift the conversation from one about national security and illegal immigration to one about the lawful act of seeking asylum.

Traditional need-based or merits-based methods of screening clients individually for services were inadequate in a situation where all the mothers and children had compelling need and compelling merits claims. At the same time, the advocates were facing an unprecedented mass imprisonment that overturned established immigration law and process. There was no time for impact litigation, and Congress had stripped Article III courts of most immigration determinations.

In response, the advocates deconstructed their traditional representation model. Eschewing a screening process, they offered representation to all the detainees, even though the lawyers were vastly outnumbered by their clients in a site where the government called the shots. That fraught decision turned out to be the key to turning the tide.

The CARA Pro Bono Project combined universal representation at the site with segmentation of the representation, breaking the work down into discrete tasks managed through a web-based client management database system. Fresh brigades of volunteers arrived at the site every week to pick up where the last had left off. Each carried the cases forward like batons until the next brigade arrived. Departing advocates joined the expanding network of experienced family detention advocates, creating a “hive mind” for both the local operation and the national strategy. This innovation allowed the project to massively expand client coverage with just a skeleton crew on the ground. But this was not the only advantage of the new model.

Shifting the Balance of Power

By representing everyone, the advocates could apply pressure on the DHS for basic access to clients and amplify to the government and the media the voices and experiences of the detainees. It gave the advocates influence over the immigration court docket, enabling them to choose which of the hundreds of cases to bring first.

The detained mothers and children started to prevail on their claims that they had a credible fear of persecution if returned—the first step in the detained asylum process. Then they began overwhelmingly to win their asylum cases on the merits. By the end of the next fall, the mothers had won nearly 100 percent of their asylum cases. The narrative that the mothers and children were lawbreakers or security threats had fallen apart, and the view that the families fleeing the Northern Triangle were bona fide asylum seekers was in ascendance.

The CARA Pro Bono Project embodies what Adjunct Professor Stephen Manning calls “massive collaborative representation”: lawyers, technology, strategy, and networks focused on a geographic site and a discrete legal issue. It magnifies the voice of the individual client and the effectiveness of the individual lawyer through collective representation that changes the way people think and talk about people and power. It fundamentally shifts the balance of power between the detainees and the government.

Of the tens of thousands of mothers and children whom the project has served, fewer than one percent have been deported. That number clearly conveys the weakness of the government’s legal argument for bypassing the asylum system. It also illustrates the success of the resistance, which was able to move 99 percent of the CARA Project clients to immigration court—where their claims for asylum could finally be heard.

More Advocate Magazine Stories

email jasbury@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-6605

Judy Asbury, Assistant Dean, Communications and External Relations

Advocate Magazine

Lewis & Clark Law School

10101 S. Terwilliger Boulevard MSC 51

Portland OR 97219