Talking life and learning with comedian Hari Kondabolu

Open gallery

By Roy Kaufmann, director of public relations, Lewis & Clark College

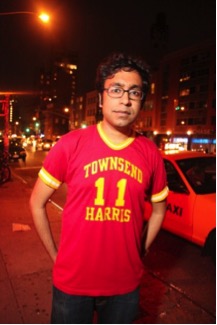

Earlier this month, with students back on campus and classes started, Lewis & Clark and APANO–the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon–cohosted a back-to-school show featuring the comedy of Hari Kondabolu.

Kondabolu is a Brooklyn-based, Queens-raised comic who the New York Times has called “one of the most exciting political comics in standup today.” In March 2014 he released his debut standup album “Waiting for 2042” on the indie label Kill Rock Stars.

With a comedic style that is decidedly highbrow and unflinchingly political, Kondabolu draws deeply upon his liberal arts education, including a degree from Bowdoin College in Maine, and a master’s degree from the London School of Economics. After his nearly 90-minute set, I sat down with Hari in the circular meditation room beneath Lewis & Clark’s Agnes Flanagan Chapel for a conversation about how the comic’s education–inside the classroom and out–has shaped his career in comedy. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Okay, our first question. How does your liberal arts education inform your comedy?

I think a lot of my jokes are structured like essays, like something I set up and I try to prove some idea. I feel like a lot of that has to do with how I was taught to write, what we see as standard essay writing in liberal arts education–like thesis, point 1, point 2, point 3, repeat thesis. Somehow the thesis is always right, not like that’s ever the case.

A lot of that shapes how I process information and organize it. The difference is there needs to be punch lines, not just a good argument. Each sentence has to be punctuated with a joke or something funny. Still that’s how I was taught to argue, and that comes from liberal arts training and education.

Did you start writing comedy when you were in college?

I started writing in high school. I grew up in Queens, NY, went to Townsend Harris High School, which was a humanities school, so [my] liberal arts education began even before I went to college. It was a public school, but a strong public school in Queens.

When did you start performing?

In high school. The one time I performed before college was at my high school’s comedy night, which I started. It was called “Comedy Night.” I was never good with titles. I started there and I thought I would stop, get it out of my system.

I went to college in Maine, at Bowdoin College, which is a fine institution. But certainly growing up in Queens and going to school in Maine was an adjustment.

And I realized I was being looked at and asked questions and poked at, and even though people didn’t have bad intentions, but they didn’t know what to do. That’s the thing with diversity, it’s often a one-way street, and for people of color it becomes this thing where we have to almost educate other people, whereas I thought we were in education together, teaching each other stuff.

I didn’t like the idea that it was on me. And so I liked standup because in standup I could stand out on my own terms. I could choose how I wanted to present myself and how I was going to explain my life, and I could ask the questions and I could answer them. So certainly standup became a really wonderful thing that nobody sanctioned. I wasn’t part of a club, it was just me, the only person on campus who did standup, and that was a big deal.

And I remember I studied at Wesleyan University my junior year, which was another incredible liberal arts university–very diverse, politically active, a great deal of creativity, and that was very good for me. And I went back to Bowdoin afterwards because the great thing about small schools is that you become really close to students, you become really close to professors, to the administration. And they flew me back twice when I was studying “away in Connecticut” and they paid me for it. And those were my first paid gigs, my college paying me to come back and perform.

And I didn’t want to leave–even though in some ways Wesleyan was a lot more fun and fulfilling to me in a lot of ways–but Bowdoin gave me a chance, because it is a small school, to know my administrators, to be close with professors.

I still have professors who are friends of mine, who’ve been mentors to me. People I could take multiple times, and they were small classes and they fit my learning style. These are things you don’t get out of bigger institutions. So certainly being in a small liberal arts college shaped a lot of my worldviews, writing style, life experiences.

You went to the London School of Economics for your master’s in human rights and started as an organizer?

I started as an organizer, working in Seattle for an immigrant rights organization. I did it for two years and planned to get the master’s in human rights to add that framework to the organizing. I felt like that would be useful, especially as we try to frame this as a human rights issue, not an immigrant rights issue or a civil rights issue, but as something that is fundamentally the same in all of us. These struggles are shared. That was the plan.

But then I got discovered in Seattle. It was actually at Bumbershoot Festival [that I was noticed] by the HBO Comedy Festival, which was at that time a big festival for discovering new talent. No one had ever heard of me because I really didn’t perform in New York, mainly in Seattle, which was my first scene.

And that led to an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live and a manager and this framework to be a professional comedian. I had all these pieces, but it wasn’t my plan. I ended up taking a year off from everything and going to get the master’s degree.

After a year there, I decided this was an opportunity that not many people get. And I never thought an Indian-American would have an opportunity to do stuff like that, just because there were no role models or anybody outside of comedy who took risks like this. I saw the tide changing. I could see it in bits and pieces, whether it was Kal Penn or Aziz [Ansari], there were these bits and pieces. Something was going on.

My kind of comedy, which was aggressively political, for lack of a better way to phrase it, and very personal and as honest as I hope I want it to be, there was room for it and I didn’t expect that. That’s how I ended up going into comedy.

I don’t think I wasted my education, but certainly it’s a different direction. But a lot of my peers are working at Amnesty [International], or the World Bank, or the U.N. I mean, I think they’re proud but I’m not really using my education in any classical sense.

It’s interesting because I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that philosophy was a free thing. In ancient Greece, [that] philosophers used to speak publicly for free and share their ideas and that was a thing people did. And now philosophy is seen as this classical thing and it’s not integrated into the mainstream.

And knowledge in general is kept at universities or kept at J-STOR; that the public at large doesn’t have access to this, even when they’re publicly funded. That Aaron Swartz movie talked a lot about this. It’s kept hidden away.

And standup, you know, allows thought to spread in a very accessible way to the public and is meant for the masses to consume, the way philosophy was meant to be. It was supposed to be the spreading of ideas and questioning things critically, and in some ways it’s wonderful, but it’s also kind of sad that standup is one of the few places that does it so directly.

It’s strange that our attention spans are so limited and yet something with no production value whatsoever can still be able to capture people’s attention. I think that there’s a longing for that, to be able to be connected to people in a certain way. And I think standup still provides that. So I suppose that in a lot of ways I think philosophy can be woven into comedy.

You play a lot of colleges on campus, and I’m sure you’re following the debate around free speech, political correctness on campus, trigger warnings. What are you seeing on campuses? What’s your take on that debate?

I think it is people who are not adjusting to the times. Political correctness, when it’s something when people are unable to comfortably speak and learn from each other, I understand that and it is frustrating.

But is that really what we’re talking about? It often ends up feeling that I can’t say whatever I want to say publicly. And you can, of course you can, and there will be repercussions. And some will say, well, these kids won’t laugh. Well, sometimes audiences don’t laugh. You adjust to them.

And also your job as a comedian when you want to stay relevant is to be able to connect to young people. That’s always the audience. If you can’t play to young audiences, you’re irrelevant. You need to be able to reach people.

When you dismiss what’s happening on college campuses, you’re saying that knowledge doesn’t create progress. You’re saying that these places that create knowledge, we don’t need that. It’s irrelevant. Which is an absurd idea. So it ends up feeling to me like people who don’t question things or get frustrated are dinosaurs now. So when I hear Seinfeld talking about this, I think, you’re not even playing colleges. What are you talking about? And you’re the one saying people are too sensitive.

There was a time when the work place and the power structure were all white. And so all of a sudden we’re in a situation where you have people of color, trans folks, queer folks, women, all sharing a space in a workplace, increasingly getting power, being able to speak up for themselves.

So what we’re calling political correctness is really just people finally questioning what’s always been said and wanting their voice to have the same weight. And, if that makes you uncomfortable or you feel it is restricting your speech, it’s not really restricting your speech; it’s allowing others to speak. And if you think allowing others to speak is restricting your speech, who has the issue here?

And I think comedians also aren’t used to criticism in debate. I mean, I think in other countries, our art form is written about more in mainstream newspapers. And when we get criticism on Twitter, comedians freak out, which is like, yeah, when you say words, you know those words create an impact on the audience. And you know that because that’s what you do for a living: create words to make an impact. You can’t assume the impact you’re going to have is the same across the board. That’s impossible, and to assume that is ridiculous.

And so now you’re making an impact, and this is how people are responding, by not laughing, writing think pieces, writing blogs, tweeting at you. That’s the name of the game, and you adjust to it.

There were times when people didn’t have to make sets for TV because TV wasn’t a thing; and then there’s radio, and when the internet happened there was an opportunity that brought comedians so much more success and fame and found their audience.

You have to adjust, and you know what? This is a challenge. What does an 18-year-old know in terms of an adult life? They’re discovering things, often for the first time, even though an 18-year-old now is considerably more educated than I was at 18 and more than 18-year-olds in the past, just because now they have access to the internet.

But, it’s your job to communicate messages, to make people laugh. And you’re not always going to have the same audiences. And audiences change from place to place and time to time. And that’s your job to figure it out. And it’s not always easy. And this is not always an easy gig and sometimes some college gigs are better than others, just like any gig.

So to me, I’m not going to discredit academia in terms of the way kids are coming out of it and the audiences. I think actually I’ve had some amazing shows at colleges.

More Newsroom Stories

Public Relations is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email public@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

Public Relations

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road MSC 19

Portland OR 97219